The Fediverse is best explained as an interconnected web of services that communicate with each other with a shared protocol. Imagine that you had an account on one social website from which you could send, receive, and reply to posts from people that use different websites with a different interface and behavior. This is a vague explanation of how federation works that skips over a lot of the technical details, but think of replying to a blog post from your Instagram account, or seeing your friends' Facebook posts in your Twitter feed.

This interoperability of common actions such as "likes", "replies", and "follows" is what unifies the majority of federated social networks; nobody loses access to friends or connections because they use a different website. The communication protocols used by these servers implement open standards, which means that they can be freely adopted, implemented, and extended by everyone. In effect, anyone can create and own a fediverse server with the ability to interact with virtually any other server using this protocol.

Technicalities

Because of the "open" nature of the fediverse, nearly all networks are developed by a community of people independent from any corporation or official institution. Most software related to the fediverse is open source, so anyone can participate in their growth and development. What is important to note, though, is that the fediverse isn't one singular thing. It consists of a huge amount of different projects, groups, discussions, and ideas.

Servers, Networks, Protocols

Fediverse servers, or "instances", are the smallest part of the fediverse, and what you'll see the most of. Because the majority of the fediverse is open source, anyone can create their own server by just choosing a domain and paying for hosting. Some people make their servers publicly available for anyone to use, others only allow access for a small group, and some individuals have one just for themselves. A list of some of the public servers you can join can be found at the-federation.info; some notable ones being mastodon.technology, digipres.club, cybre.space, witches.live, and toot.cat.

Most of these federated servers can be categorized by the software that they use. While they all accomplish the same goal of being a social network, there are many different interfaces or implementations of the federated protocols that various people have written. Some of the more popular examples include Mastodon, Pleroma, Friendica, Pixelfed, write.as, and Socialhome.

Protocols are the communication standards that these federated servers can use to communicate with each other. The dominant protocol is currently ActivityPub, but OStatus and DFRN do exist as well. To provide features that aren't a part of the protocol, certain networks can deviate from the protocol(s) they support to provide endpoints and functionality that other software won't know how to use. For example, one fictional project called "Hands" could provide a "poke" button to send useless notifications to people. As far as I know, the ActivityPub protocol doesn't specify a "poke" button, so users would only be able to poke people on the "Hands" network (someone on a Mastodon server would be out of reach). This is somewhat rare, though, as even in cases where some functionality might not translate to other software as effectively, most developers do their best to maintain compatibility with the rest of the fediverse.

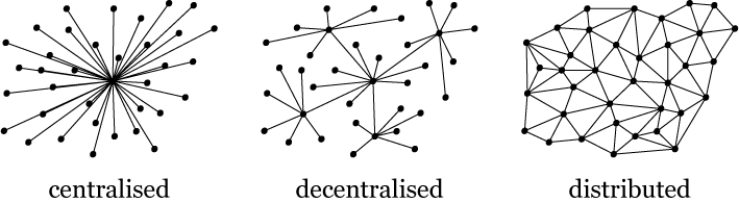

Distributed vs. Decentralized

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Decentralization_diagram.svg

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Decentralization_diagram.svg

One notable point about the fediverse's construction is that it does not create a completely decentralized social media - it's still subject to some of the same issues and caveats of some centralized services, but it caters to a lot of the concerns that someone looking for a decentralized service might have. To quote Chris McCormick, "decentralization is a means to an end, not an end in itself."

distributed: when separate systems coordinate. placement of authority is a differentiating factor of their design.

decentralized: distributed system that can elect to defer or migrate central authority. mutable actions may be negotiated.

federated: distributed system that has nomadic and often competitive authorities. actors negotiate their own activity at any point.

One of the heaviest criticisms of this model is that, instead of trusting a known mega-company like Facebook or Twitter to facilitate your online identity, you now rely on a random stranger to keep their server running and appropriately moderate their instance. This brings me to two points:

1. The owner of your instance is not supposed to be a stranger.

This obviously differs depending on which social groups you are a part of, and some of the larger public instances definitely stray from this condition, but (in my opinion) the advantages of federated networks are much more effective when those networks are kept relatively small. Imagine a private instance for a specific neighborhood or a hobby organization - or just a random group of friends.

Darius Kazemi gave a talk back in August titled "Trust is Not Harmful", in which they describe a lot of their experiences and motivations for creating friend.camp, a small Mastodon instance for a bunch of their friends to explore the advantages that decentralized social media can offer. This presents a few different ideas about how this technology can be used - notably, the software can be customized to fit the needs of its specific users (for example, dolphin.town), and the owners/users of the instance can more effectively exchange trust with each other.

I'll come back to that first idea later on, but the latter brings up an important distinction: smaller groups are much easier to moderate. In a social network, it's far easier to split up the governance and rules of "what you're allowed to say on the internet" between various groups, because not all groups have the same social guidelines of what they deem to be acceptable in their community. A lot of what you should say depends on who you're talking to - it's not necessarily wrong to discuss your hobby of combining peanut butter and celery, but you might get a few strange looks if you bring it up obsessively in your local book readers' club. If you aim to disrupt reading time with your vegetable preachings, the threat of being removed from the club will probably keep you in line. Quoting Darius, "decentralized networks map somewhat cleanly onto real human networks, and it's the social relations and the trust built into them that hold the key to building something valuable."

Another point that is brought up is that it's far easier to moderate a smaller community when you actually know every person in the network and are able to sit down and talk to them - and this brings benefits for the users of that network as well. Rather than waiting for an overworked moderation team or trusting an obscure automated program to review a post, you actually know the specific person to get in contact with if something goes wrong - and unlike the CEO of Twitter, they actually have the time to respond to each of their users.

2. Even a stranger might be more trustworthy than the social media companies we know.

I mentioned an exemption to the condition of a federated instance owner being a stranger in the case of many of the large public networks that exist, and a lot of people question what the difference between a huge instance like mastodon.social and any centralized network like Twitter would be. For this, I have to point to some of the ideals of the Mastodon community and a lot of their users' reasons for moving away from these larger services in the first place.

The first reason is that companies like Twitter have a fundamental need to profit from their users. A good portion of the fediverse is funded almost entirely from community donations and the generosity of their creators, so they don't need to resort to some of the larger platforms' methods of large-scale advertising and data hoarding in order to break even. So even if you have to trust a stranger on the fediverse, a lot of the users there think it's better to trust someone you don't really know than rely on a company that's exploiting your online presence to make a profit. Sam the sandwich man might have a strange moustache, but at least he isn't going to capitalize on my human need for social interaction.

Another reason is its approach to an online presence - particularly, how it handles privacy and the "Right to be Forgotten". A lot of the fediverse has a fairly strong opposition to the archival or indexing of their posts/profiles, and many subscribe to the idea that their content should be something that eventually disappears. This is also reflected in their approach to implementing a search box: "Lack of full-text search on general content is intentional, due to negative social dynamics of it in other networks" - @Gargron@mastodon.social. Some of the potential reasons for supporting this viewpoint are made pretty clear in wilkie's post about Social Archival; that, even if some content might be public, it doesn't necessarily mean the authors have given consent for anyone to do whatever they want with it.

Finally, perhaps the most practical reason that the fediverse can be useful is because of its software. Mastodon and Pixelfed are well known for maintaining accessibility standards; both have supported image captions for a long time, and their developers put a great deal of effort into designing an interface that can be used by everyone. It doesn't end there, though - tying this back to the first idea from Darius Kazemi's talk, I have to emphasize that nearly all of this software is open source. This means that, if you're hosting your own instance for a group or community, you can change how it works. This is a benefit of open source that I deeply appreciate: the ability to create functionality for a small group or even a single person that just wouldn't make sense for anyone else. Do you want to make the "reply" button lock you out of the interface for 15 minutes so that you can really think about what you want to say? Remove all of your notifications in place of a daily email digest to cut down on anxiety? Go ahead! Noone can stop you. Just remember to use your newfound powers for good.

Deplatforming and Free Speech

Because fediverse instances are managed individually, moderation is largely left to the owner of the server you're using or interacting with. When you use someone's network, the owner is granting you access to share your thoughts through their server - it isn't an inherent right, and it can be taken away. However, this largely depends on the views of the owner, and most will try to contact users to come to an agreement before enforcing an outright ban.

This is a very political topic but, in my experience, arguments for free speech on social networks are generally not really arguing for "free speech" as the term is defined. They're arguing to restrict the power of people who own social instances to control the content that their network shares and promotes. When you join a fediverse instance - or rather, any social network - you submit yourself to the governance of its owner to make the moderation decisions of whose content you can see and which instances you interact with. It's okay for people to share their opinions, but it's also well within the right of a social community to refuse to accept them. Disallowing this would mean creating a social network without a "block" button - it would mean creating a law to prevent people from covering their ears while you scream about conspiracy theories over corn subsidies.

FLOSS levels the “free speech” playing field because the code - speech - can be modified and redistributed freely with no special benefits or harms for the originating developer nor for the forking developer. In this context, the cries of “violating free speech” are laughably lazy; an unhappy user can fork it and have their speech - code - compete fairly. It isn’t censorship of the user, because once more the user - who has developer-like capabilities in the FLOSS world - can fork and compete on a level playing field.

- @cj@mastodon.technology, cjslep.com

This point is relevant because of issues that much of the fediverse community had with Gab creating their own Mastodon instance and beginning to federate with other servers. I won't go over all of the controversy, but the gist is that many Mastodon instances and other developers refused to federate with Gab because of their political association, sparking massive backlash from Gab's community complaining that Mastodon was "Deplatforming" them and "infringing on their rights". Most of these arguments were based on the idea that the Mastodon project shouldn't be able to assert their political standing, and that social networks are some kind of public-domain service that everyone deserves an equal share in. To people that think this: your right to free speech is not a right to free audience. You can decide what comes out of your mouth, and I can choose whether or not to listen to it. Being banned from one social network doesn't tape your mouth shut, won't prevent you from using the internet, and certainly isn't a human rights violation. But I digress...

Broken Federation is Okay

One of the reasons that some people argue against federated social networks is that this federation can be broken by instance-level blocks like those which have been implemented for Gab. An issue that John Henry points out is that the federated model implicitly couples moderation with a user's identity. If another network is deemed inappropriate by your federated instance, then no interactions with users on that network will be visible to you unless you specifically follow them. However, as Robert Sharp explains, this problem doesn't have to be as big as it seems.

In the case of Mastodon, the limits of the federation model might be a strength. A semi-permeable social network, which restricts access to certain instances, might be perfect for children and schools, for example. And of course there will be iterations to the software that improve on the current solution and perhaps give more control to individual users.

- Robert Sharp, robertsharp.co.uk

Yes, if you join a social network, you're subject to the views and judgement of its owner - but that's nothing new. Twitter, YouTube, and almost all social websites in existence all have their own terms of use and moderation teams that review what you say. Nobody should be in charge of moderating their own posts, and treating all people differently in a federated model would create far too much work for the network's moderators. A fully distributed social network is unrealistic, and centralized networks give too much trust to a single party - I restate: federation is a compromise, not an ideal.

In Conclusion

It isn't perfect, but...

I believe I've hinted at this point a few times throughout this post: decentralization is not a universal solution to all problems on the web. There might be some nice aspects that it provides, but just as the freedom to do as you want can be a feature, a lack of governance and regulation can be a problem too. The fediverse is a nice halfway mark between a centralized and distributed service that gives you the freedom of federation with the practicality of a centralized site, but there are obvious problems with giving everyone free self-hosted software for them to do whatever they want with (Gab being a prime example of this, in its use to facilitate misinformation and hate speech).

Of course, decentralization has its good sides - creating tools to overcome actual censorship by an oppressive government, for example - but it is important to acknowledge that it has negative aspects as well. Luckily, most developers in the fediverse seem to understand this, and put a lot of care into creating systems that can empower their users to regulate these behaviors as much as they facilitate them.

Join the Fediverse!

I didn't realize it when I started writing this, but a lot of the summarized information I wanted to provide in this post already exists over at runyourown.social - so if this has gotten you interested in joining or creating a federated social network, I highly recommend checking that site out. fediverse.party also contains a bunch more useful resources and information about these projects.